Master Photographers on Their Art

I have always been uncomfortable with the phrase “taking pictures.” I think it’s all wrong. Mostly I think there is an understanding that takes place during a portrait session between the photographer and the subject. For us both it’s more about an exchange, giving rather than taking. My portraits are the result of conversation.

The human face signals our emotions, suggests our cultural background. It is the naked part that we present to the world; our faces speak realms about our identity. Our faces anchor us to our histories, our stories, and the stories of our ancestors. Our faces change with time and our faces absorb the passage of time. We tell our stories through our faces: how we present ourselves, how we use this personal canvas to convey not only our emotions, but also histories and identities.

When taking a portrait, I rarely look into the ground glass of my camera except to momentarily check composition. I engage my sitters—we speak for far more time than I photograph. At certain points in our conversation I will photograph. It must be instinctual by now, but also I hope it creates spontaneity. Most of my frames are made looking at, and interacting with, my sitters.

Portraits are unusual situations as people are not usually experienced in having strangers get this close. I tend to work close. But I think I’m open in conversation with people, which is where we meet each other, and by the time we start the portrait session they are open to it. It’s rare for anyone to recoil or deny access.

I can only count three or four situations—in nearly thirty years of photography—where people reacted badly to me being so close to them. There is a reason I like to work in this space. It is very intimate. Sometimes, the subject is amused, which may be a foil. It’s the space where usually we only allow loved ones. It’s a place to respect.

I have received requests not to reproduce certain images for all sorts of different reasons. What we see when we look at our reflection in a mirror, and when we look at a photograph, are often two very different images.

I once photographed the French philosopher Hélène Cixous. She was so worried about the results, which I sent to her, that she wrote to me and said that to reproduce these images was to her tantamount to rape. I still have the letter. It seems to me that if you have any sense of social responsibility in a case like this, then you withdraw the session—and this is what I did.

I don’t ever approach a sitting to put anybody in a good or a bad light. Even the sessions I have made with despots and mass murderers, I wouldn’t seek to portray them in a bad light. It seems cheap and too easy to do. I don’t really feel that the portrait sitting is about subjecting any one of my subjects to a bad experience. It is a shared experience. I’m not sure that trying to describe a “true face” gets us anywhere; there isn’t such a thing. We present many faces to people every day. The most a portrait photographer can hope for is to make a portrait that reflects where the sitter is with the photographer, what knowledge they have shared, what the photographer has seen.

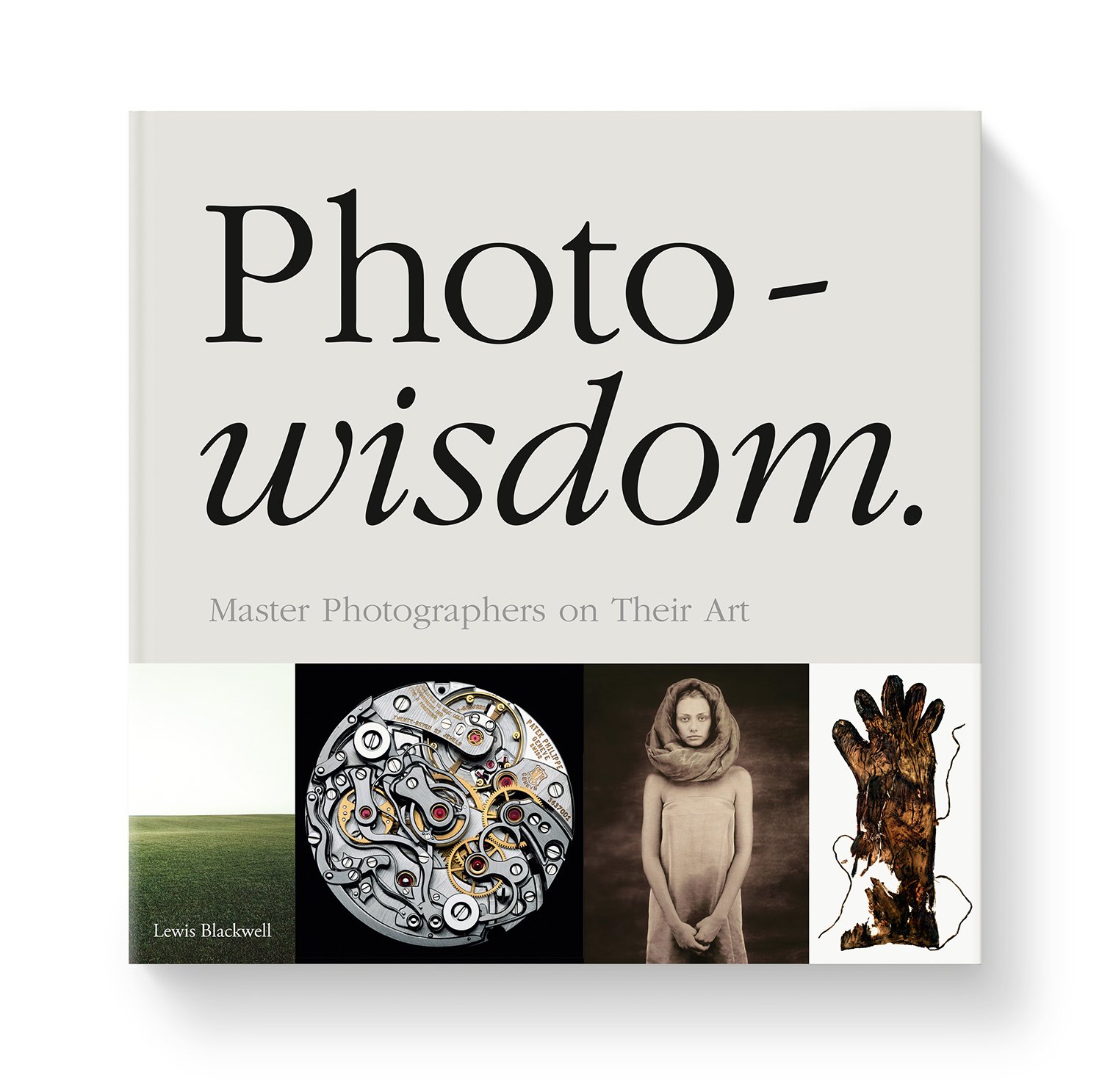

From PhotoWisdom: Master Photographers on Their Art by Lewis Blackwell. Copyright by the photographer, reproduced with the permission of the publisher Blackwell & Ruth.

From PhotoWisdom: Master Photographers on Their Art by Lewis Blackwell. Copyright by the photographer, reproduced with the permission of the publisher Blackwell & Ruth.