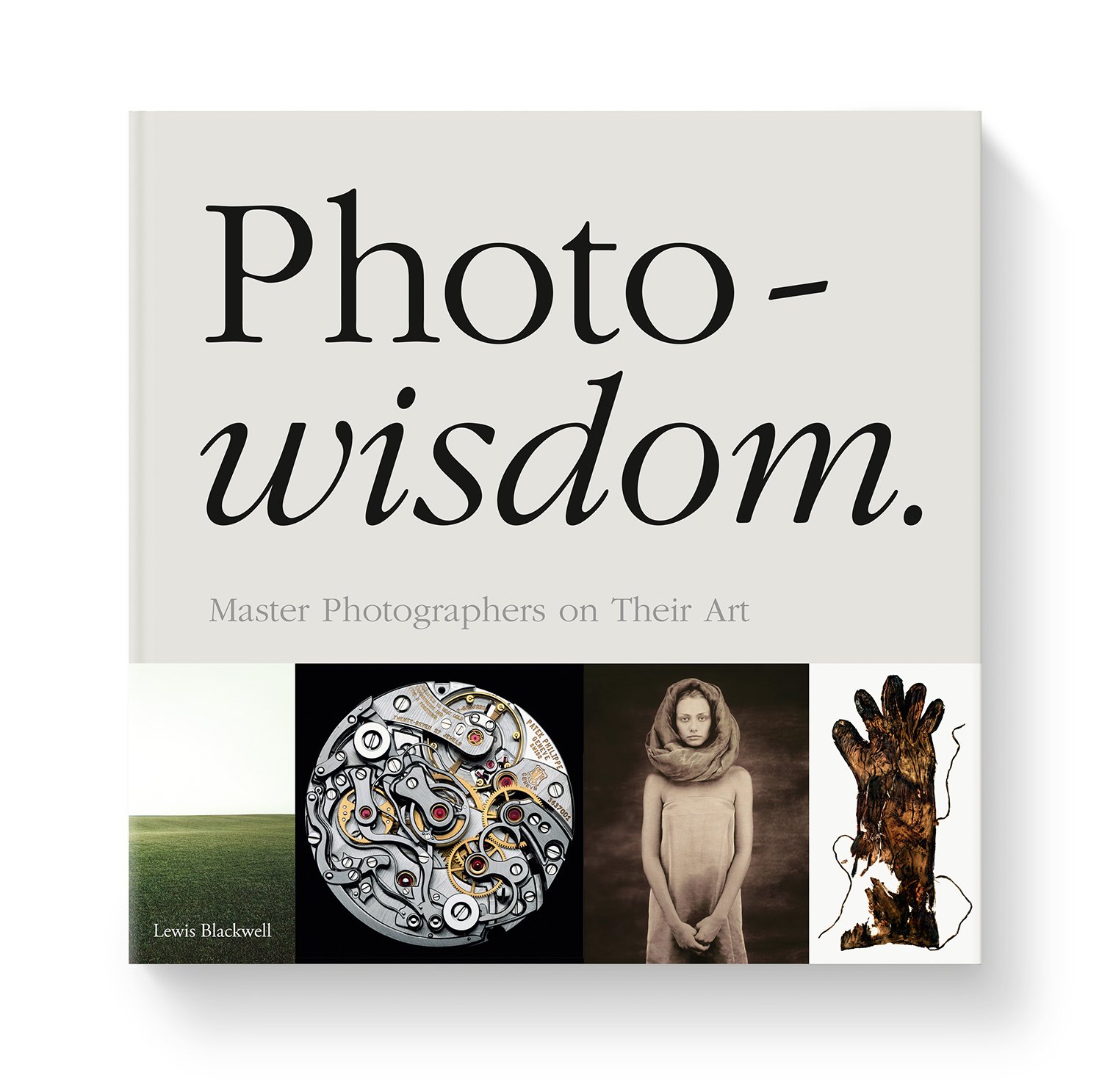

Master Photographers on Their Art

It is one thing to photograph a group of people, it is another to try to understand them. For that you need time, and patience, and an innate respect for difference – the gulf between your own religion, politics, economic status, language, and those of the person in front of you. Trying to bridge that gulf with a camera invites suspicion and misrepresentation. But, at a time when traditional photographic coverage is often limited to a brief stopover and a search for sensational images, the need to take time and represent and understand the people whose lives and values are very different from our own is greater than ever.

WHY DO YOU TAKE PHOTOGRAPHS?

The photographic process offers me the opportunity to delve into issues that I do not fully understand, or those which I believe have been rendered in a skewed fashion. I generally start with a premise, a kind of supposition, which I expect to be tested by the photographic engagement. I spend a great deal of time considering how the work might counter or broaden preconceptions we have about various situations. My expectation is that by remaining open to what is presented in the process of making, that this will inform the final document or image. In general, I choose topics which strike a personal chord with me and which I believe deserve to be discussed. My hope is that the time spent dwelling upon a given issue will yield an understanding which counters or expands upon preconceptions; offering a bridge across the religious, cultural, national and political divides which threaten to forestall understanding.

WHEN/HOW DID YOU DISCOVER THAT THIS MEDIUM WAS FOR YOU?

In college I studied visual art and had the opportunity to study with Emmet Gowin. Although the medium of photography was perhaps of less importance, I soon realized that the process of making art offered the opportunity to engage with aspects of my heritage and with issues about which I cared a great deal. The political and social dimension soon mingled with an introspective component of the work, and photography eventually seemed to me to be the best suited to that inquiry. I met a group of individuals who encouraged the artistic exploration and endeavour – regardless of whether it would be able to sustain one in a material way –and I found this offered to me a great source of sustenance in a psychological and intellectual realm.

YOU ARE DESCRIBED AS A DOCUMENTARY PHOTOGRAPHER. HOWEVER, YOUR IMAGES AVOID MANY AREAS OF DOCUMENTARY AND FOCUS ON THE PORTRAIT.

I am uncomfortable with the divisions imposed upon the practitioners of photography and the ideological constraints which such labels impose. Why should a work be limited to the realm of documentary, art, portraiture, fashion or journalism? Could we not imagine works which transcend those boundaries and which may fall within the sphere of various headings? I want the work to provoke a dialogue between our expectations of a subject, or even a mode of working. I try to make images that are respectful of their subject, that render them in an empowering way. I use the aesthetic qualities of the image – the formal aspects – to entice the viewer to engage with the image and, with luck, to encourage him/her to want to know more about the subject about which the work was created. In terms of portraiture, in the strict sense, I imagine that the strength of any given image is borne by the quality of engagement between the person making the image and the sitter. The way in which a person presents themselves to the camera – comfortable with a life lived in their skin – is invariably far more compelling than anything that the photographer could concoct in his imagination. In that regard, the photographic act is one of recognition and receptivity, rather than one of grand invention.

WHO OR WHAT INSPIRES YOU IN PHOTOGRAPHY?

I have been far less interested in individual photographers and their work than I have been in the lives and priorities of some of the photographers who have drawn my interest. Invariably, I am drawn to image-makers who have spent their lives engaged with their subject in a determined and unique manner, with little thought given to how the work would be received in the current climate. From my perspective a work can only last, or remain resonant, when it comes from a genuine inquiry on the part of the artist. Artists and writers who have sustained that inquiry throughout their careers are the ones that I turn to for inspiration.

WHAT MIGHT BE YOUR ADVICE TO A YOUNG DOCUMENTARY PHOTOGRAPHER?

It is difficult to know how to offer advice from the extremely specific perspective I have about making work. But what I found most encouraging when starting as a photographer was the notion that there was value in the endeavour, and that young artists should have the latitude of several years to spend carving out their own perspective; that the answers and the means by which to articulate one’s concerns are not granted quickly. I wish for the pressure of production to be removed and for there to be a kind of grace period within which the expectations of others are reduced. I think this was the most important kind of encouragement I received: not to be influenced too greatly by what is fashionable at the moment, but rather to try and unravel what exactly it is I would like to say by spending so much time creating work. When spending so many years dedicated to something, I could only hope that it is in the service of that which we care about deeply. In 2001, curious about the possibilities of expanding the scope of the work and wishing for it to be accessible outside the framework of traditional publishing practice and museum exhibitions, I conceived of a series of projects – entitled the International Human Rights Series – that would engage an international audience, furthering their understanding of complex human-rights issues around the world. In the intervening years, the projects have taken a variety of forms – books, films, exhibitions – and are disseminated as widely as possible, using means that offer an alternative to commercial publishing and distribution. As part of the ideology behind the series, where possible the projects have been offered in their entirety online, where they may be read free of charge. Books are also available in bookshops at a subsidized price and for sale over the Internet. Each project results in at least one publication and is distributed through a network of institutions concerned with human rights and the humanities, through political and cultural groups and non-government organizations. The projects are distributed free of charge by these institutions and brought to the attention of the media and relevant political representatives.

From PhotoWisdom: Master Photographers on Their Art by Lewis Blackwell. Copyright by the photographer, reproduced with the permission of the publisher Blackwell & Ruth.

From PhotoWisdom: Master Photographers on Their Art by Lewis Blackwell. Copyright by the photographer, reproduced with the permission of the publisher Blackwell & Ruth.