Master Photographers on Their Art

I had wanted to become a magazine photographer when I matriculated in 1948. However, at that time there was virtually no magazine photography in South Africa. For a short while I apprenticed myself to a man who had claimed he was a magazine photographer and would teach me, but I ended up going to weddings with him. My job was to bump any guest with a good camera to make sure my boss was the only one to get good pictures. That was rather discouraging, so I went into working at my father’s shop, but I maintained my interest in photography.

During the fifties things started happening and I took it upon myself to be a missionary with a camera. It seemed to me that nobody else was taking any notice of what was happening. I sent some work, some primitive sort of photographs, to Picture Post in London. They were politely rejected. But then when the ANC’s Defiance Campaign began, the editor Tom Hopkinson cabled me to send any photographs that I could. This was a gift from the heavens, to have a kind of assignment from the magazine. But I was hopelessly inexperienced; my pictures were very poor. I realized I had no burning interest in capturing events as a photographer; my interest lay in the conditions that led to the events. As a citizen of the country, I was obviously very interested in the events, but as a photographer I was not cut out to be a photojournalist. I tried to teach myself some technique – I bought books and improved my techniques sufficiently to become reasonably adept with a camera and get predictable results. At my father’s death I sold the family business, and I had a choice: I was then thirty-two and was tempted to become a lecturer in economics, but I wasn’t really that strong in mathematics. I also wanted to experience the world at first hand, physically. I wanted the smell, taste and touch of things. Photography offered that. On 15 September 1963, I handed over the keys of the shop and started to call myself a photographer.

I realized early on there were things I needed to do simply because I had a burning need to do them. It was a time of great conflict and I needed to explore. If you look through my work it is more or less a straight-line graph; I am a monoculture. I have been plugging away at more or less the same thing over the years: I am interested in our values, our ethos. I regard myself as an unlicensed, self-appointed social critic. I guess that approach has been with me pretty well all along. It’s like an itch: something begins to nag at me until I go out and look for a photograph.

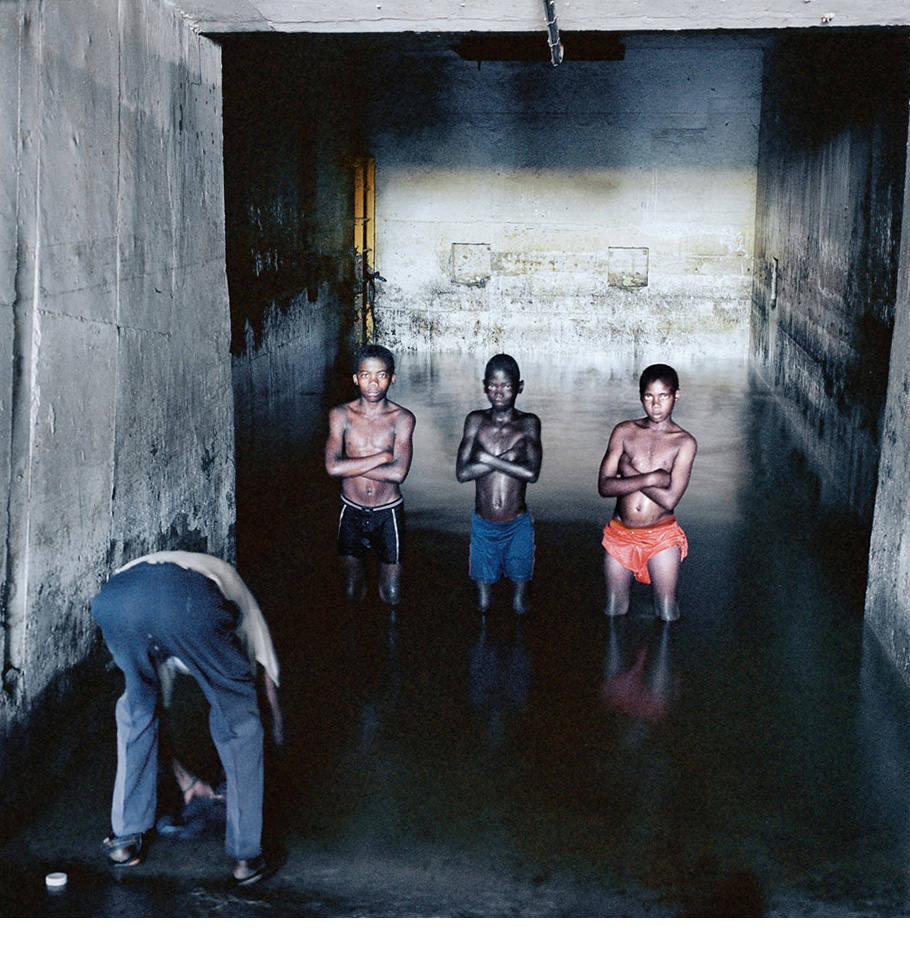

This is a country in which the contradictions are sometimes mind-blowing. Some of the people I photographed in my first book, Some Afrikaners Photographed, were almost racist in their blood, in their genes. And yet I found moments with them of extraordinary spiritual generosity to the black people that they lived among. A more physical generosity than you ever found in my white-pink compatriots in the wealthier suburbs of Johannesburg.

For a long time I had little or no contact with other people through my photography. I didn’t publish. I was an amateur, a failed would-be magazine photographer, and I just put my photographs away in boxes. When I became a full-time photographer I felt liberated, and wanted the work to move on, and, in part, for people to publish it. But I don’t think that has ever been the driving force behind doing the photographs. It is more that the camera provides a justification for looking at things in a way that the ordinary citizen is not able to, or doesn’t have the opportunity to, or is even not allowed to. When you are working with a camera, you have a kind of licence to look. It is the act of looking, or seeing, that is the most important thing. Quite often I realized it did not really make much difference if I finally took the photograph or not. It was sufficient to recognize the moment, the occasion, the thing that moved me. But exhibition and publication are important. Nowadays, I am entangled in the art market and selling prints has become important – not that I personally attach significance to it, but it is a way of earning a living. You have to be wary of it, though: it is a real danger that you might take photographs because you know they could sell – and to me that is the kiss of death.

The end of apartheid did not really change anything about how I approach my work. It did not call for a new phase of work because I am interested in values, so I am just as interested in post-apartheid values. Of course, there is no question that the transition into democracy has been enormously interesting and I have moved into new photographic fields, albeit with the same photographic eye.

I work frequently now in colour, which I had done as a professional almost from the beginning, 1964, but I did not use colour in my personal work until the turn of the century. There were a few reasons for that. During the years of apartheid I found that colour photography was too sweet. At that time it seemed you could not avoid sweetness with colour, particularly because you would use colour transparency film, over which you had little control. If the exposure was right then the colours tended to be deeply saturated and quite pretty. But in the 1990s I began to work with some new colour negative films, and they had a flexibility that I previously had not found. I also became familiar with the techniques of digital reproduction and knew what could be done. In the last decade I have worked with the help of somebody who is a specialist in digital reproduction, and I find that together we can make colour prints that come very close to my sense of the light here and of this place. It has been liberating for me as it means I can spend more time making photographs.

I am doing more photographs now relating to what might be called landscape than I did before. During apartheid I did not do much of that kind of thing because I felt it was somehow self-indulgent. These subjects did not signify for me at that time in the way they do for me now. Today I don’t mind if I spend days travelling through remote parts of the country just photographing bits of land.

I can sometimes travel for two days through the countryside and see nothing, in the sense that I don’t stop once and say to myself, “That is something I want to photograph.” I am not seeing, I am not engendering that response in my cortex. Then I will see something, or get a feeling of something in the air that I need to probe. So I might stop and walk around and kick a few rocks, break a few blades of grass and generally become more frustrated, and then drive on. And maybe I will get 100 kilometres down the road and I will take a photograph. There is a strong intention in all this. When I finally get to see something, I become aware of how it sits in the landscape and I feel a way of bringing it together. There is almost an inevitability about the way it will come together in the photograph.

The captions with my photographs are enormously important to me. I may change captions over time as my views change or I think of a better way of expressing myself. I do not regard the photographs as pure pieces of art that exist in a vacuum – they are things snatched out of the real world, and I am not ashamed to put with them the basic questions of what, where, who and when.

My photography of South Africa does come from the fact that I am viscerally related to this place. I can’t help that. It’s an accident of birth and I don’t have that connection, that understanding, with other countries. For my personal work I restrict myself – I don’t want to go outside of South Africa. There is more than enough to engage me here for my life.

From PhotoWisdom: Master Photographers on Their Art by Lewis Blackwell. Copyright by the photographer, reproduced with the permission of the publisher Blackwell & Ruth.

From PhotoWisdom: Master Photographers on Their Art by Lewis Blackwell. Copyright by the photographer, reproduced with the permission of the publisher Blackwell & Ruth.